Skinamarink (2022): A Shudder review

Skinamarink

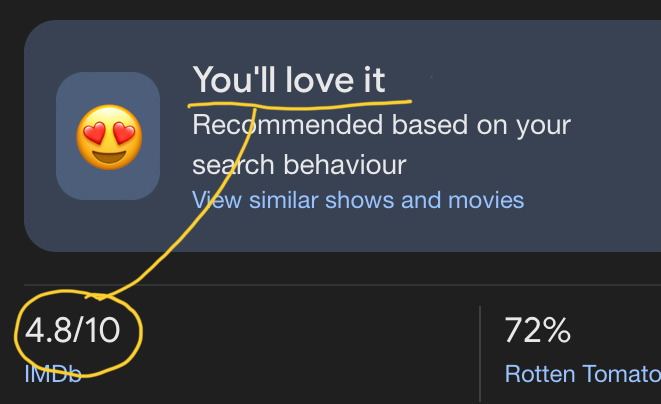

Going into Skinamarink (2022), I knew absolutely nothing about it other than it was incredibly divisive. Having finished it, my uninfluenced opinion solidly front of mind, I treated myself to a quick peek at the IMDB rating to gather the public consensus. In doing so, I caught a stray from Google using it as a vehicle to insult my taste in movies.

So, with that context, I’ll come straight out and say it: I did like it. Passive-aggressive Google was right. I don’t think it was perfect; I have reservations and criticisms, but, predominantly, I found it incredibly refreshing. However, more than any other movie I’ve enjoyed, I completely understand that some people might think it was the worst movie they’ve ever seen.

SKINAMARINK

To describe Skinamarink with a synopsis befitting a traditional movie is somewhat redundant. The gist is that two kids are trapped in their home as it is contorted by an unknown presence. More accurately, Skinamarink is an experience. It’s an experimental horror that could comfortably be found in a gallery, and perhaps find itself better received. Skinamarink avoids traditional filming conventions, diverting from narrative arcs and character building to focus instead on curating discomfort and unease.

I can best describe Skinamarink as looking into a mirror in the dark (for 90 minutes).

HYPNOTIC UNDULATIONS AND MOUNTING DISCOMFORT

The strength of Skinamarink is also its shortcoming. I think it would be a disservice to call Skinamarink’s schtick a schtick, but the grainy, static-y, extreme claustrophobic close-ups of dark corners, doorways, and edges of furniture for the entire run of the movie are simultaneously its success and downfall.

At first, I found the intense dark, undulating static hypnotic. You’re just there, staring at a shot of a skirting board in the dark for 15 seconds in complete silence. Then, during the next 15 seconds, you’re trying to discern a fuzzy triangle in a new, but very similar, section of grainy darkness. Finally, you discover the triangle is a lampshade before being shown yet another obfuscated mundane object.

After ten minutes or so, when I realised this was it, this was all we were getting, I felt the long-forgotten thrill of potential. These guys were doing something I hadn’t seen a hundred times already. More impressively, they were doing something I had never seen. This was interesting. This fuzzy bit of ceiling was one of the most exciting shots I’d seen in horror in a long time, and I had no idea where they were going to take it.

After about thirty minutes, I realised they’d painted themselves into a corner. This is what they had committed to. This had to be the whole film, and I wasn’t convinced it was sustainable. The delight was slowly transforming into concern; being unable to ditch this premise meant we were in for 90 minutes of intimate, inanimate close-ups. I wanted Skinamarink to stick the landing, but I couldn’t think of a resolution that would pay off and remain true to the vision.

Skinamarink’s pacing was symptomatically awkward. The excitement was wearing thinner and thinner, saved only by the expectation that something more had to happen… it couldn’t just end.

And then it was over, and I was relieved. I was relieved that the uneasy feeling it gave me was over but I was also relieved that I didn’t have to watch it anymore because it is simultaneously incredibly interesting, effectively emotionally manipulative, and tediously boring.

TOO SCARED TO LOOK AT THE SCREEN

I don’t remember the last time I couldn’t full-frontal a horror movie. In recent years, can’t remember being startled or watching something between my fingers; you watch enough horror, you know what’s happening and when. Typically, we get one of three jump scares:

Mounting terror jump

Mounting terror, fake relief jump

Suspiciously quiet jump

That’s it. That’s all we get. All predictable, all somehow equally telegraphed.

In the last 15 years, the movie that came closest to getting an inadvertent physical reaction from me was Hereditary (2018). Specifically, the scene of Peter waking up in the dark with Toni Colette spiderman’d onto the ceiling. That almost got the caveman fight or flight rumbling inside of me. But then again, I have a slight fear of Magic Eye pictures; my anxiety builds in the moment the image starts to appear, in case I’m suddenly confronted with something looking back at me. I have a substantial dislike of things hiding in plain sight.

For me, it was notable to find myself watching a scene in Skinamarink through the thin cotton of my t-shirt, which I’d gleefully pulled over my face for protection. Sadly, and perhaps ironically, it was a reaction to one of the only things in Skinamarink that wasn’t very original, and yet it was still masterfully executed: a little kid taking an excruciatingly slow look under a bed in the dark, on the instruction of a disembodied demonic voice. Heightened by the thick, eerie unease the film was layering upon the audience over the last hour, it was an unbearable watch (thank you).

IS Skinamarink more than close-ups?

Yes. It’s strange because I don’t think I would feel an obligation to talk about similar elements of another horror in a review like this, but tiny moments in Skinamarink feel like they hold such a weight that they deserve discussion, almost in defence of the movie against harsher critics. Perhaps it’s the strange configurations of time and pacing, or maybe the general ambiguity of Skinamarink, but moments with the children, even when inferred, feel uniquely heavy. Not because we care about them, there’s never any time dedicated to getting to know anyone, but because Skinamarink so effectively conveys what it is like to be a child alone with the terrors of an empty house at night. Not by telling, not by showing the children’s experience, but by eliciting those feelings in the audience themselves.

I really liked Skinamarink. I will never watch it again.